There is a huge tropical rainforest in northern South America that occupies the drainage basin of the Amazon River and its tributaries and covers an area of 2,300,000 square miles (6,000,000 square km). It is limited in the north by the Guiana Highlands, to the west by the Andes Mountains, to the south by the Brazilian central plateau, and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean.

The Amazon Rainforest is the world’s richest and most diverse biological reservoir, with millions of insect, plant, bird, and other species, many of which are still unknown to science. There are numerous species of myrtle, laurel, palm, and acacia trees, as well as rosewood, Brazil nut, and rubber tree, among the lush greenery. The mahogany and the Amazonian cedar provide excellent wood. The jaguar, manatee, tapir, red deer, capybara, and many other rodents, as well as various varieties of monkeys, are among the major animals in the forest.

- The Amazon rainforest – Ecosystem

- Central and Northern Andes and the Amazon River basin and drainage network

- Types of Forests

- Abiotic conditions

- Flora and fauna

- Amazon Basin and Amazon Biome

- An Amazon downpour’s unpredictability

- The Amazon is a place where dreams and reality collide.

- Amazon Deforestation

- Initiatives to Combat Deforestation

- Uncontacted People of Amazon Rainforest

- The Awa tribe of Brazil

- The Kawahiva Tribe

- FAQS

The Amazon rainforest – Ecosystem

Brazil’s fast rising population inhabited vast portions of the Amazon Rainforest in the twentieth century. As a result of people clearing land to extract lumber and build grazing meadows and farmland, the Amazon jungle declined rapidly.

Brazil holds over 60% of the Amazon basin within its borders, with forests covering 1,583,000 square miles (4,100,000 square kilometres) in 1970. By 2016, forest cover had decreased to roughly 1,283,000 square miles (3,323,000 square kilometres), or about 81 percent of the area covered by forests in 1970.

The Brazilian government and various foreign organisations began working in the 1990s to protect areas of the forest from human encroachment, exploitation, deforestation, and other types of devastation. Although forest cover in Brazil’s Amazon continues to fall, the rate of decline has slowed from around 0.4 percent per year in the 1980s and 1990s to roughly 0.1–0.2 percent per year between 2008 and 2016.

However, 75,000 fires broke out in the Brazilian Amazon in the first half of 2019 (an increase of 85 percent over 2018), owing in part to Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s encouragement, who is a major proponent of tree clearance.

Central and Northern Andes and the Amazon River basin and drainage network

Amazon is the world’s largest river basin, with a forest that runs from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Andes’ forest canopy in the west. From a 200-mile (320-km) front along the Atlantic to a 1,200-mile (1,900-km) wide belt where the lowlands meet the Andean foothills, the forest spreads out. The significant rainfall, high humidity, and consistently high temperatures that exist in the region reflects in the rainforest’s vast size and continuity.

Ecuador initiated a unique plan in 2007 to preserve a portion of the forest within its borders, which is located in Yasun National Park (established 1979), one of the world’s most biodiverse regions: the Ecuadoran government agreed to forego the development of heavy oil deposits beneath the Yasun rainforest (worth an estimated $7.2 billion) if other countries and private donors contributed half of the deposits’ value to a UN-administered trust fund for Ecuador. Ecuador, on the other hand, cancelled the proposal in 2013, after only $6.5 million had been donated by the end of 2012. Petroecuador, the country’s state-owned oil firm, began drilling and extracting petroleum from the park in 2016.

A few quick facts

1. India is twice the size of the Amazon biome.

2. The Amazon River stretches for about 6600 kilometres.

3. It is home to 10% of the world’s known species.

4.There are 350 ethnic groups who call it home.

5. In the last 50 years, 17% of the forest cover has been lost.

Natural and cultural richness are both important.

The enormous number of animals, birds, amphibians, and reptiles4 found throughout the biome is also astounding. The Amazon is home to more than 30 million people who live in nine distinct national political systems across a large expanse.

According to the Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA), indigenous people make up around 9% (2.7 million) of the Amazon’s population, with 350 ethnic groupings, more than 60 of which are still entirely isolated. Despite its enormity and apparent distance, the Amazon Biome is unexpectedly delicate yet near to each of us.

Putting a pillar of life on Earth in jeopardy

The seemingly limitless Amazon has lost at least 17 percent of its forest cover during the last half-century, its connectivity has deteriorated, and countless indigenous species have been subjected to waves of resource extraction. The Amazon’s economic transformation is gaining traction, based on the conversion and destruction of its natural habitat. However, as those factors gain power, we are discovering that the Amazon serves a key role in preserving regional and global climate function, a contribution that everyone, affluent or poor, relies on.

The canopy cover of the Amazon helps regulate temperature and humidity, and it is intricately related to regional climate patterns via hydrological cycles that rely on the forests.

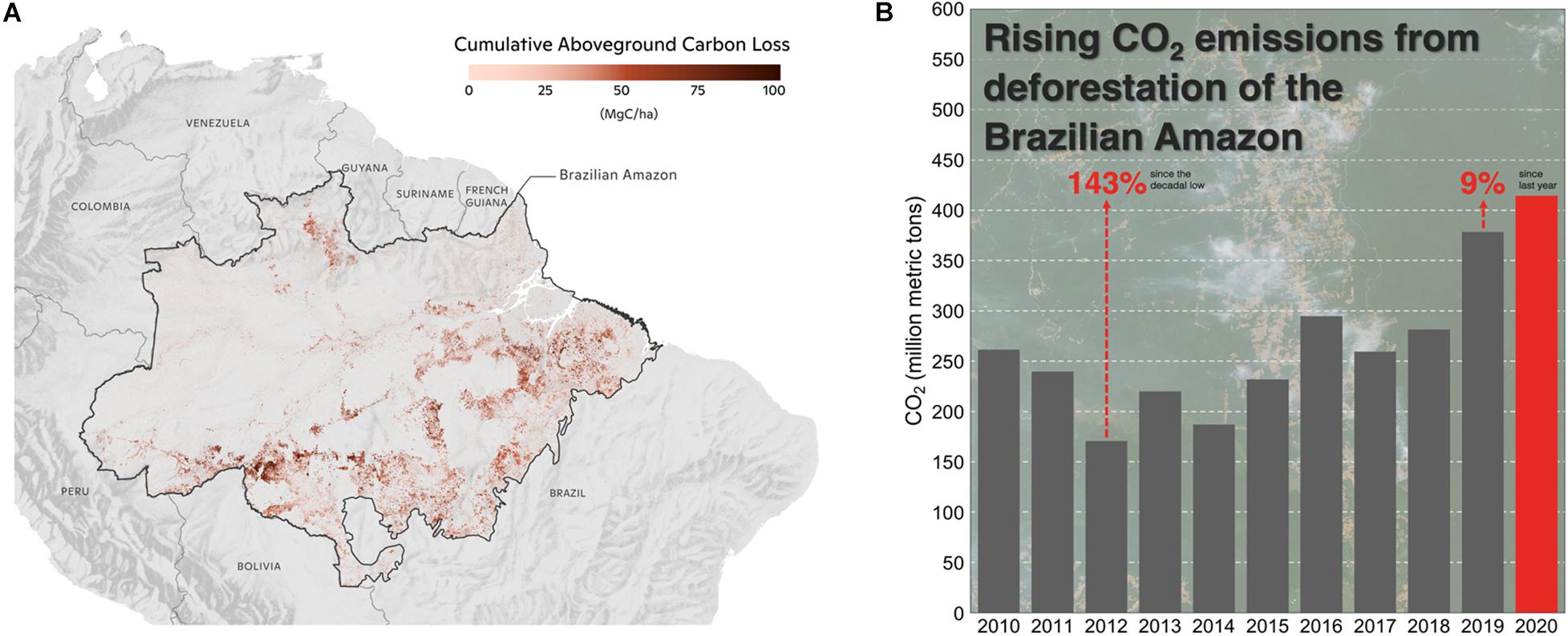

Given the large amount of carbon store in Amazonian forests, there is a significant risk of global climate change if we do not preserve or manage them adequately. The Amazon has 90-140 billion metric tonnes of carbon, and releasing even a small amount of it will drastically accelerate global warming. Land conversion as well as deforestation in the Amazon currently emit up to 0.5 billion metric tonnes of carbon per year, not considering forest fire emissions, making the Amazon an essential player in global climate regulation.

Types of Forests

Forests can grow wherever summer temperatures above 10 degrees Celsius (50 degrees Fahrenheit) and annual precipitation exceeds 200 millimetres (8 inches). Within these climatic bounds, they can develop under a range of conditions, and the types of soil, plant, and animal life vary depending on the extremes of environmental forces.

Hardy conifers such as pines (Pinus), spruces (Picea), and larches (Larix) dominate forests in chilly high-latitude subpolar zones (Larix). These forests, known as taiga or boreal forests in the Northern Hemisphere.These have lengthy winters and get between 250 and 500 mm (10 and 20 inches) of rainfall per year. Mountain ranges in many temperate regions of the world are under the coverage of coniferous forests.

Mixed forests

These comprising both conifers and broad-leaved deciduous trees predominate in more temperate high-latitude areas. Broad-leaved deciduous forests grow in middle-latitude settings with an average temperature of at least 10 degrees Celsius (50 degrees Fahrenheit) for at least six months of the year and annual precipitation of at least 400 millimetres (16 inches). Oaks (Quercus), elms (Ulmus), birches (Betula), maples (Acer), beeches (Fagus), and aspens (Acer) dominate deciduous forests with a growing period of 100 to 200 days (Populus).

Tropical rainforests

They thrive in the equatorial belt’s humid weather, supporting remarkable plant and animal richness. Heavy rainfall encourages broad-leaved evergreens rather than needle-leaved evergreens. Monsoon forests are tropical deciduous forests that grow in locations with a long dry season followed by a substantial rainy season. The temperate deciduous forest reappears in the Southern Hemisphere’s lower latitudes.

Species composition (which varies depending on the age of the forest), the density of tree cover, the kind of soils present, and the geologic history of the forest region defines the forest types. Altitude and specific weather conditions (see cloud forest and elfin woodland) influences the forest development.

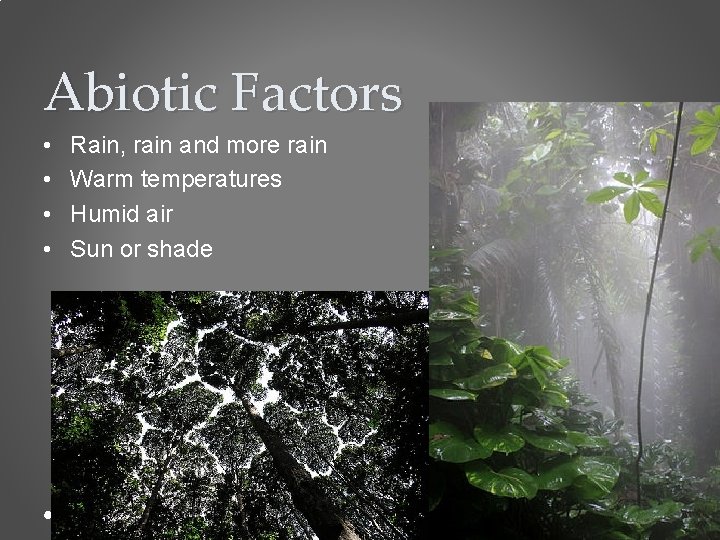

Abiotic conditions

Depth, fertility, and the existence of perennial roots are used to classify soil conditions. Soil depth is significant because it controls how far roots may penetrate the earth and, as a result, how much water and nutrients are available to the trees. The taiga has sandy soil that drains swiftly. On the other hand, we have brown soil in deciduous forests, which is nutrient-richer than sand and less porous. A soil layer rich in iron or aluminium is common in rain forests and savanna woods, giving the soils a reddish or yellowish colour. Tropical rainforests’ soil is frequently poor due to the large amounts of rain they receive, as nutrients are swiftly leached away.

The amount of water accessible to the soil, and thus to tree development, is determined by the amount of rainfall received each year. Evaporation from the surface or leaf transpiration can both cause water loss. Evaporation and transpiration also regulate the temperature of the air in forests, which is always slightly warmer in the winter and slightly cooler in the summer than the surrounding air.

The density of tree cover influences the amount of sunlight as well as rainfall reaching each forest layer. A fully canopyed forest absorbs between 60 and 90 percent of available light, the majority of which is used for photosynthesis by the leaves. The velocity of falling water that penetrates down to the ground level by flowing down tree trunks or dripping from leaves is slowed by leaf cover, It tends to reduce the velocity of falling water that penetrates the ground level by dropping from leaves or trickling down tree trunks.Because water that is not absorbed by tree roots for nutrition travels down root channels, water erosion is not a significant effect in sculpting forest topography.

Flora and fauna

Forests are one of the world’s most complex ecosystems, with substantial upright position. Coniferous timberland have the simplest structure, with a tree level rising to more or less 30 metres (98 bases), a light or missing shrub level, and a lichen-, moss-, and liverwort- covered ground subcaste. The tree cover in evanescent forestland is separated into upper and lower stories, whereas rainforest cover is divided into at least three strata. In each of these timbers, the timber bottom consists of a subcaste of organic matter that sits on top of mineral soil. Extreme heat and moistness degrade any organic matter present in tropical soils, affecting the ground level. Fungi on the soil exterior have an important function in the accessibility and distribution of nutrients in northern coniferous woodlands. Some fungus work in collaboration with tree roots, while others are parasitic and destructive.

Amazon Basin and Amazon Biome

The Amazon Biome is defined as an area primarily covered by thick wettish tropical timber, with infinitesimal patches of other green similar as grasslands, field timbers, champaigns, wetlands, bamboos, and win timberlands. The biome covers6.7 million square kilometres and is partook by eight nations (Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, and Suriname), as well as French Guiana’s overseas habitat. Complete corners extend outside the biome and may incorporate biomes from other biomes ( dry wood, cerrado and table).

It’s not simply the lush greenery.

Is the Amazon River Basin, then, just a vast, homogeneous area of jungle divided by a big river? Such a view of the area only scratches the surface of what is a very complex and dynamic environment in actuality. Likewise, many different landscapes and ecosystems make the basin.

These are some of them:

The Amazon River Basin was formed as a result of the Earth’s movements.

The Amazon River used to flow from east to west, flowing into the Pacific Ocean millions of years ago. About 20 million years ago6, the Andes Mountains began to rise along the eastern side of the South American continent (owing to significant pressure on the tectonic plates), blocking the passage of the Amazon River.

Freshwater lakes grew as a result, and the river’s flow gradually reversed to its current eastern course. Around 10 million years ago, the river reached the Atlantic Ocean near the Brazilian city of Belem.

The water cycle is a natural mechanism that is extremely efficient.

Moreover, the Amazon jungle experiences tremendous rainfall every year, ranging from 1,500 to 3,000 mm.

What’s the source of all that water?

In the Amazon River Basin, evapotranspiration – the loss of water from the soil via evaporation and by transpiration from plants10 – accounts for roughly half of the rainfall, with the other half attributable to eastern trade winds blowing from the Atlantic Ocean.

Furthermore, If evapotranspiration and its function in ecological balance disrupts, the climate in the region – and far beyond – will be severely damaging.

An Amazon downpour’s unpredictability

Rainfall in the Amazon River Basin follows a seasonal pattern, and precipitation varies greatly from one location to the next, even within the basin’s core.

For example, the Amazon River city of Iquitos in Peru receives an average of 2,623 mm of rain per year, while Manaus in Brazil receives 1,771 mm and has a severe dry season.

The Amazon is a place where dreams and reality collide.

Our comprehension of the major ecological benefits rainforests provide to the local and global population grows as our knowledge of the Amazon grows.

While many people associate a patch of rainforest with instant gratification – some merely to put food on the table – others regard it as a repository of biodiversity, important chemical compounds, or even carbon stocks for the world’s rising carbon dioxide emissions.

Amazon Deforestation

After a 22 percent increase from the previous year, the area deforested in Brazil’s Amazon reached a 15-year high (2020).

According to a previous study, Amazon forests have started to emit CO2 rather than absorb it.

Global climate change and rising deforestation will very likely influence the Amazon’s forests, water availability, biodiversity, agriculture, and human health over time, influencing the region’s forests, water availability, biodiversity, agriculture, and human health.

Cattle ranching

It is one of the main causes of deforestation in the Amazon.

Beef eating is one of the primary causes of deforestation in the Amazon Rainforest.

Large expanses of forest are cleared to make pasture land for grazing cattle by cutting down trees and burning the forest down. Additionally, with 1.82 million tonnes supplied to the United States and China in 2019, Brazil is a big beef exporter.

Agriculture on a Small Scale

Agriculture on a Small Scale is a type of farming that is done on a small scaleIt’s been blamed for deforestation in the Amazon Rainforest for a long time.

In addition , small-scale agriculture, like ranching, needs “slashing and burning” of the forest to make room for crops and grazing. Not only this but It is causing deforestation in the Amazon Rainforest.

Moreover, small-scale agriculture, like ranching, necessitates “slashing and burning” of the forest to clear the area for crops and various sorts of grazing.

Fires

The Amazon, unlike other types of woods, did not evolve to burn. As a matter of fact deforestation contribute to flames in the Amazon basin.

Rainforests have a lot of wetness, as their name implies, which helps to protect them against fire.

Agricultural operations in the Industrial sector

Industrial agriculture is becoming more popular in the Amazon Rainforest.

There are many other reasons.

Mining operations for sought-after resources like gold inflict further damage to the Amazon jungle.

Loans and infrastructure spending, such as roads and dams, have been raised by the government.

Initiatives to Combat Deforestation

Brazil was one of numerous countries that vowed to end and reverse deforestation by 2030 at the COP26 climate meeting. The LEAF (Lowering Emissions by Accelerating Forest Finance) Coalition was announced during the Leaders Summit on Climate in 2021.

Initiatives within the REDD+ programme:

It is one of the climate change mitigation alternatives in poor nations for preserving forest carbon stocks, managing forests sustainably, and lowering emissions from deforestation and forest degradation.

Uncontacted People of Amazon Rainforest

Uncontacted peoples are communities or groups of indigenous peoples who live without regular contact with their neighbours or the rest of the world.

In the first place those who choose to remain uncontacted are known as indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation. Estimating the total number of uncontacted tribes is difficult due to legal safeguards. Although estimates from the UN’s Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the non-profit Survival International put the figure between 100 and 200 tribes with up to 10,000 people.

Equally important, the majority of tribes are in South America, especially Brazil, where the Brazilian government and National Geographic believe that there are between 77 and 84 tribes.

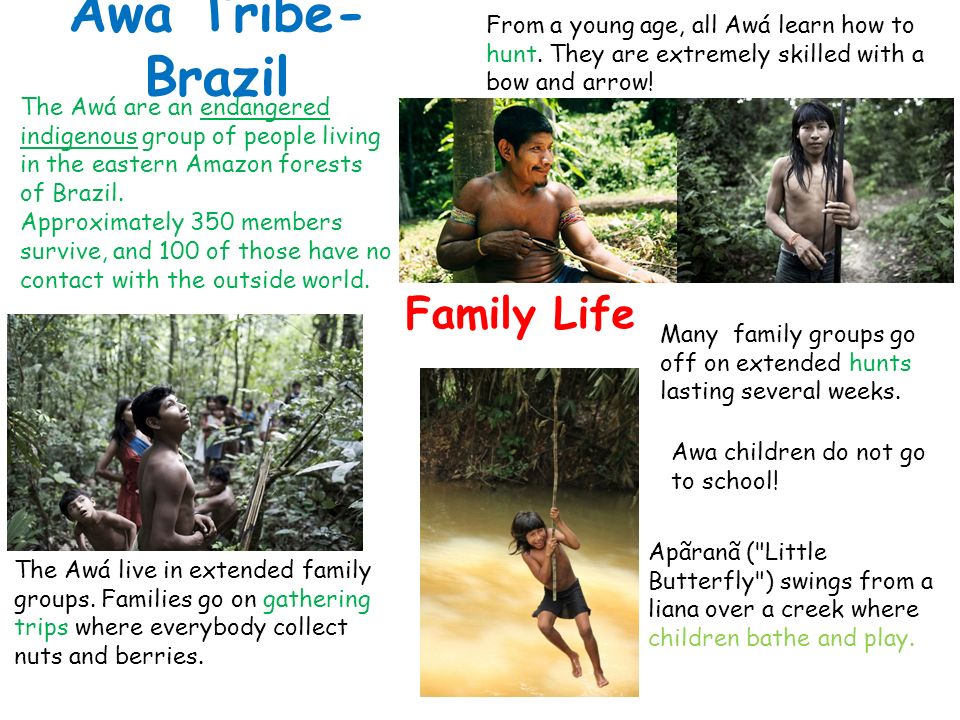

The Awa tribe of Brazil

The Awá are a people who live in the Amazon rainforest’s eastern reaches. As a matter of fact there are around 350 members, with 100 of them having no outside contact. Because of conflicts with logging interests in their territory, they are considered critically endangered.

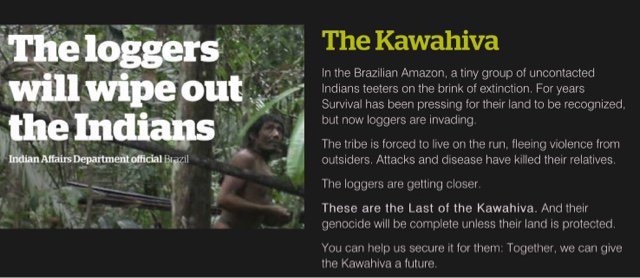

The Kawahiva Tribe

The Kawahiva people live in Mato Grosso’s northwestern region. They are always on the move and rarely interact with others.

As a result, physical evidence such as arrows, baskets, hammocks, and community dwellings . And this is the primary source of information about them.

The Korubu live in the western Amazon Basin’s lower Vale do Javari. Moreover, the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau and the Himarim are two further tribes that may exist. In the Uru-Eu-Uaw-Uaw Indigenous Territory, Kampa Indigenous Territory, and Envira River Isolated Peoples, there may be uncontacted peoples.

In 2019, a few isolated gatherings of one to two persons caught the attention of the media. The Piripkura tribe’s two brothers continue to live alone in the jungle. Moreover, they made touch with FUNAI after an 18-year-old fire went out. They were the subject of the documentary Piripkura that followed. Furthermore, another man, dubbed “the man of the holes” by his neighbours. He lives alone on 8,000 acres of land where he has excavated hundreds of holes for farming and trapping.

Furthermore, uncontacted peoples in Brazil are under risk from illegal land grabs, loggers, and gold miners as of 2021. With Jair Bolsonaro’s government signalling its intention to develop the Amazon and shrink indigenous reservations.

FAQS

Q 1. Why is the Amazon rainforest in danger?

In the first place Loss of biodiversity: Species lose their habitat, or can no longer subsist in the small fragments of forests that are left. … not only this but also Habitat degradation: New highways that provide access to settlers and loggers into the heart of the Amazon Basin. As a matter of fact they are causing widespread fragmentation of rainforests.

Q 2. What are 3 facts about the Amazon rainforest?

Nearly two-thirds of the Amazon rainforest is in Brazil. Moreover, the Amazon have 2.5 million species of insects. By the same time more than half the species in the Amazon rainforest live in the canopy. Furthermore , 70 percent of South America’s GDP comes from a areas that receive rainfall or water from the Amazon.

Q 3. Why is the Amazon rainforest special?

The Amazon is the most biodiverse terrestrial place on the planet. However, this amazing rainforest is home to more species of birds, plants and mammals than anywhere else in the world. Furthermore, the Amazon is also home to hundreds of endemic and endangered plant and animal species.

Q 4. Who is cutting down the Amazon rainforest?

As a matter of fact Cattle ranching is the leading cause of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. In Brazil, this has been the case since at least the 1970s. Furthermore, government figures attributed 38 percent of deforestation from 1966-1975 to large-scale cattle ranching. Today the figure in Brazil is closer to 70 percent.

Q 5. What is the biggest problem in the Amazon rainforest?

Deforestation. One of the largest, and most well known problems in the Amazon is that of deforestation. While trees have been cut for logging, development and human expansion. However, It is actually farming that is causing the most extreme and drastic deforestation among much of the Amazon rainforest.

Q 5. Do humans live in the Amazon rainforest?

The “uncontacted tribes”, as they mostly live in Brazil and Peru. The number of indigenous people living in the Amazon Basin is poorly quantified. Moreover Some 20 million people in 8 Amazon countries and the Department of French Guiana are classified as “indigenous”.

Q 6. What 9 countries span the rainforest?

The Amazon forestspans across 9 countries

The Amazon forest includes Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname and the French Guiana

Q 7. What are the three biggest threats to rainforests?

Not to mention Logging interests cut down rain forest trees for timber used in flooring, furniture, and other items. Not only this but power plants and other industries cut and burn trees to generate electricity. The paper industry turns huge tracts of rain forest trees into pulp.

.